This investigation was conducted as part of the project “Promoting reliable information and fighting disinformation in Latin America,” funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Factchequeado and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union*.

When Elon Musk appeared at the White House with a bruise near his eye on May 30, 2025, content quickly circulated on Telegram and Instagram linking the owner of Tesla and X—then a U.S. government official—to the “Black Eye Club,” a QAnon conspiracy theory that claims elites and politicians traffic children to use their blood as an elixir of youth. Around 56,000 people in messaging channels with phone numbers from the United States, Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela received these messages within hours.

With similar speed, theories about alleged climate manipulation by organizations such as USAID traveled from the U.S. to Latin America, with messages reaching 88,000 people in just a few days.

These are some of the findings we identified in the weekly REDESCover newsletters published from January to December 2025 by the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA), a nonprofit organization allied with Factchequeado, which monitors public WhatsApp and Telegram groups through the Palver platform, as well as other social networks, to identify and analyze viral content (which often includes disinformation) circulating in English, Spanish, and Portuguese.

At Factchequeado, drawing on those 2025 REDESCover newsletters and our own fact-checks, we reconstructed the path some of that viral content followed across messaging apps to identify key disinformation cases that moved between the United States and Latin America.

Among what we observed, we found that, more than language, ideological alignment was what facilitated the circulation of these narratives in 2025. We also confirmed that falsehoods go viral following controversial, high-impact news events—such as elections, political trials, or assassinations—and how high-profile figures help spread them and expand their reach.

Inside the Monitoring

Unlike social media, what circulates on WhatsApp is not directly determined by algorithms because it depends on what each person’s contacts send or forward; however, the content of those messages can originate in everyday conversations, in what spreads through the media, or on social networks (where algorithms do influence what people see). Among Latinos, WhatsApp usage (56%) is almost double that of Americans overall, and it is the fourth most-used platform among Hispanics, according to 2024 Pew Research Center data.

“We can think of WhatsApp as a platform that provides the infrastructure of everyday life. It organizes much of what we do day to day—for ourselves, for others, and for society,” says Argentine scholar Mora Matassi, who holds a Ph.D. in Media, Technology and Society from Northwestern University. She adds that “not being on this platform can come to be associated with risks of social exclusion,” so disconnecting from it “generates a lot of distress and a lot of practical complications in people’s lives.”

The public groups monitored by DDIA share in common that they actively share information, disinformation, and hyperpartisan content, featuring phone numbers with U.S. area codes (+1) as well as other Latin American countries. At the beginning of 2025, DDIA reported that its monitoring covered 1,400 public groups on WhatsApp and Telegram, but by December it had expanded to 3,300 groups, with more than 702,000 participants from all 50 U.S. states.

Luis Fakhouri, Palver’s co-founder and COO, explains that the platform makes it possible to view messages posted in public groups on messaging apps and to infer their location based on the area code of the phone number, without identifying the user. “We can access a public group and see everything that’s being said without knowing who the person who sent the message is.” What can be identified is whether that same user participates in other public groups—for example, if they express a pro-Trump or anti-Trump position—or whether the messages were generated by a bot or automatically.

According to Roberta Braga, DDIA’s founder and CEO, “the conspiracy theories observed in 2025 within the thousands of public WhatsApp groups monitored by DDIA were scarce and, despite the high transnational virality of some narratives, such as the ‘Black Eye Club’ or those related to USAID, it is important to recognize that conspiracy theories like these do not represent the majority of what is discussed in the groups.” She adds that “what is noticeable is that uncertainty and high distrust in elites and institutions lead to the dissemination of conspiracy theories, and that is a regional (as well as global) problem.”

Below, we describe the false stories that crossed borders across the Americas.

USAID and the Alleged Global Conspiracies

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) for years funded projects in humanitarian assistance, health, agriculture, and education in several Latin American countries (including Colombia, Venezuela, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Peru, and Mexico) as well as on other continents, including Africa. However, since Donald Trump moved to dismantle USAID at the beginning of his second term, numerous cross-border conspiracy theories have emerged about how the agency’s funds were supposedly used.

That the sky is now “clearer” because USAID was dismantled. That there are “no more chemtrails.” In February, in just one week, more than 88,000 Spanish-speaking Telegram users saw similar messages claiming that USAID’s money was used to generate chemtrails—alleged chemicals dispersed by airplanes to poison the population or synthetically alter the climate.

It all began, DDIA explains, with a video of a man filming a plane crossing a clear sky and questioning the absence of what he believes are chemtrails. “Conspiracy theorists promoting this fabricated theory claim that USAID was behind the toxins and that, since its dismantling, it has ceased its illicit operations,” DDIA notes, adding that “the merging of these two global-control threads—one portraying USAID as working against the public interest and the other fueling fear of chemtrails—” was also detected in Spanish on X.

DDIA also identified narratives claiming that USAID used its money to promote a left-wing agenda in Brazil. Elon Musk echoed the “deep state” narrative, claiming that it orchestrated President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s 2022 victory. As we have explained at Factchequeado, the “deep state” is a conspiracy theory that alleges governments are controlled by a network of officials or government agencies. According to DDIA, these false claims about USAID in Brazil quickly spread on social media in Portuguese, English, and Spanish, and Trump-supporting Latinos also helped amplify them.

At Factchequeado, we identified other pieces of misinformation that traveled between the United States and Latin America about USAID, involving alleged sex-change programs or events related to trans people. For example, Karoline Leavitt, the White House press secretary, falsely claimed in February that $47,000 had been allocated for a trans show in Colombia and $2 million “for sex changes in Guatemala”—a claim debunked by fact-checkers at La Silla Vacía and Agencia Ocote, both members of the LatamChequea network, like Factchequeado.

Migration and Crime

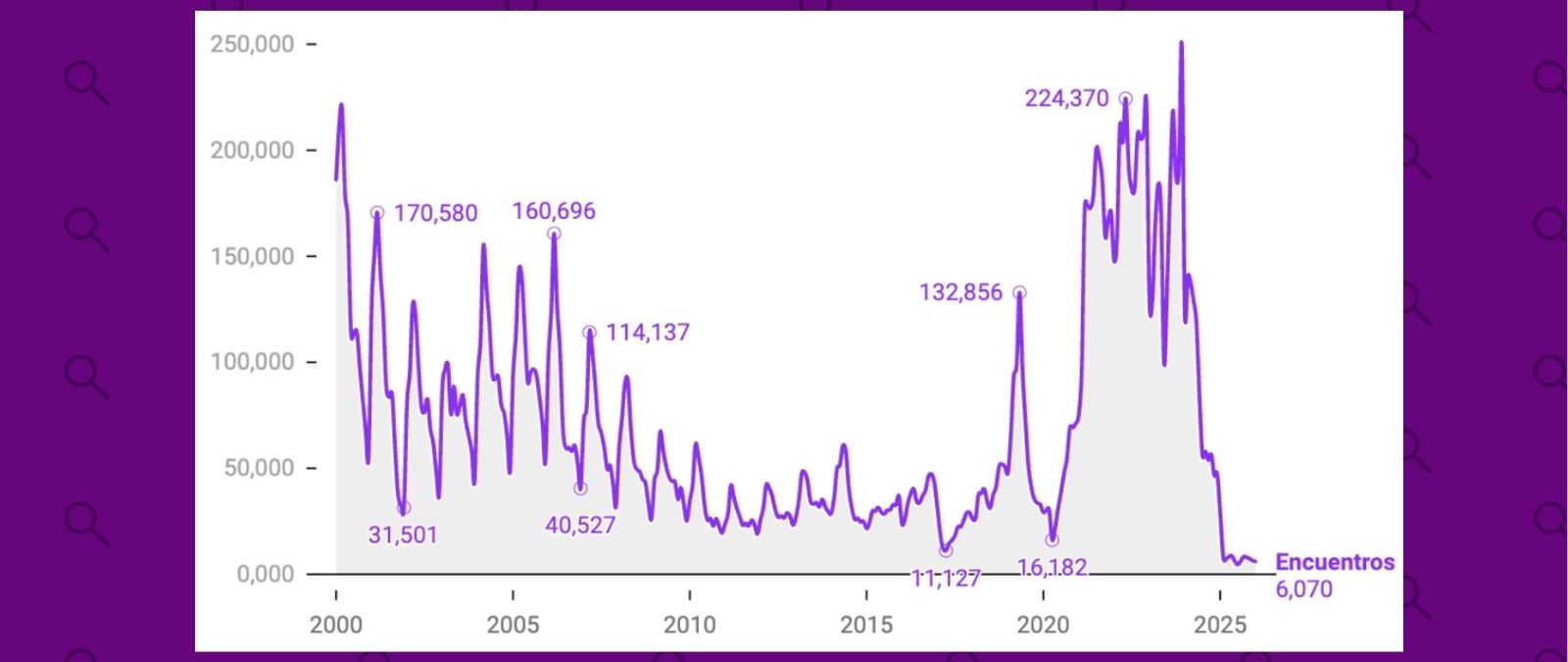

The claim that all immigrants are criminals, or that crime increases because of migration, has been a recurrent disinformation narrative promoted in the United States by Trump and some Republican politicians for years. However, as we have explained at Factchequeado, immigrants (with or without legal status) have lower incarceration rates than U.S.-born citizens. In addition, there is no statistical evidence showing that immigrants have increased violent-crime rates in the cities where they settle.

In March 2025, after invoking the Alien Enemies Act, the Trump administration detained and transferred 238 Venezuelans to CECOT (the Terrorism Confinement Center) in El Salvador, accusing most of them of belonging to the Tren de Aragua criminal gang. In reality, only six of those detained had convictions for violent crimes.

That “unverified gang labeling” became another of the narratives traveling between the United States and Latin America. DDIA describes how a post by right-wing influencer Eduardo Menoni—based in El Salvador—claiming that all Venezuelans deported to CECOT were members of Tren de Aragua generated around 77,000 interactions in messaging groups.

“False claims linking immigrants to gangs or cartels remained constant. With no evidence, viral posts suggested that all migrants were violent criminals, increasing fear and stigmatization,” the July 23 REDESCover report states. It adds that, just as in the first quarter of 2025 Tren de Aragua was consistently present in group conversations, by the second quarter other criminal groups—such as Mexican cartels—were already being mentioned.

The Tren de Aragua issue, however, went viral again after U.S. attacks on Venezuelan boats in the Caribbean Sea that, according to the Trump administration, are linked to drug trafficking, along with rising tensions between the United States and Venezuela. Among the content that circulated, DDIA identified between November 11 and 18 at least 1,000 unique messages “that could have reached 11 million Spanish-language app users across 176 groups,” about the imminent threat of a U.S. military intervention in Venezuela—as in fact occurred with the extraction of Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces on January 3, 2026.

Electoral Integrity and Cross-Border Narratives

Claiming that an election was "rigged" or that "fraud occurred" is a frequent tactic used to contest electoral results. As Factchequeado has previously detailed, this is one of ten recurring electoral disinformation patterns observed globally for nearly a decade.

DDIA found that unsubstantiated allegations of electoral manipulation were employed in 2025 to undermine the integrity of national and local elections across the Americas, specifically in Ecuador and New York. The newsletters also revealed that left-leaning candidates have been baselessly labeled "communists," as happened in 2024 with Kamala Harris during the U.S. presidential campaign.

Ecuador: Daniel Noboa’s re-election as president. In the context of Daniel Noboa’s re-election in April 2025, right-wing accounts framed a vote for Noboa as a “bulwark” against communism, while left-wing groups and politicians spread fraud allegations and demanded recounts, despite international observers dismissing any claims of electoral manipulation.

In the week leading up to the vote in Ecuador alone, messages questioning the integrity of the process—or focusing on ideological divisions and alleged foreign influence—went viral on messaging apps. At least 490 unique messages circulated in 109 public WhatsApp and Telegram groups, with a potential reach of about three million Spanish speakers in the United States, according to DDIA, which also says these messages were shared by supporters of opposition candidate Luisa González, who questioned the legitimacy of the result.

New York: Zohran Mamdani’s election as mayor. In the United States, New York City’s mayoral campaign showed how Spanish-language disinformation narratives about electoral fraud traveled across borders. In the final week of the campaign, DDIA identified at least 315 unique posts in Spanish about Mamdani, averaging 356 interactions per post. Ideological attacks and Islamophobic rhetoric gave rise to conspiracy theories accusing him of benefiting from “electoral fraud” and “foreign interference” on election day. At Factchequeado, for example, we debunked the claim that Mamdani said he would impose Islam as the city’s official religion or “eradicate Christianity” from the city.

Other Spanish-language message chains identified by DDIA included narratives about dark money funding or ties to businessman George Soros, founder of the Open Society Foundation.** They also found that in Argentina—where Trump ally Javier Milei is in office—the outlet La Derecha Diario amplified, without evidence, the testimony of people who supposedly had “voted illegally six times” for Mamdani.

Brazil: the trial of former President Jair Bolsonaro. In WhatsApp and Telegram messaging groups, DDIA identified a “trilingual digital storm” (English, Spanish, and Portuguese) in which right-wing networks portrayed the trial of Brazil’s former president—over allegedly conspiring to remain in power after losing the most recent election to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—as “political persecution.”

Republican politicians such as Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Florida Rep. María Elvira Salazar contributed to this narrative, which soon spread in Spanish and Portuguese among WhatsApp users. More than 140 unique messages (between August 25 and September 3 alone) described the former Brazilian president as a “political martyr” facing a corrupt judiciary. The messages also accused Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court of “torturing” him and claimed that “no drug trafficker has ever been put through this.”

According to DDIA, messages circulating in the groups claimed that “not a single article of the law” was being applied in the trial that ended with Bolsonaro being sentenced to 27 years in prison in November 2025. Right-wing Spanish-language influencers from other countries, such as Agustín Laje (Argentina) and Eduardo Menoni (El Salvador), argued that the justice system was being used as a political weapon, and the term “lawfare”—the use of legal systems to damage an opponent—went viral in WhatsApp groups within the Brazilian diaspora and in Hispanic communities in Florida and New York. DDIA also reported that slogans such as “Free Bolsonaro” and “Democracy died in Brazil” spread as part of a transnational far-right narrative that labels legal checks on power as authoritarian acts.

The idea that Bolsonaro’s arrest is part of a “global campaign” of “legal warfare” targeting right-wing leaders was promoted by U.S. commentators such as Michael Shellenberger and Glenn Greenwald. DDIA researchers said this sub-narrative drew parallels with Trump’s recent legal battles and warned of coordinated efforts by “global elites.”

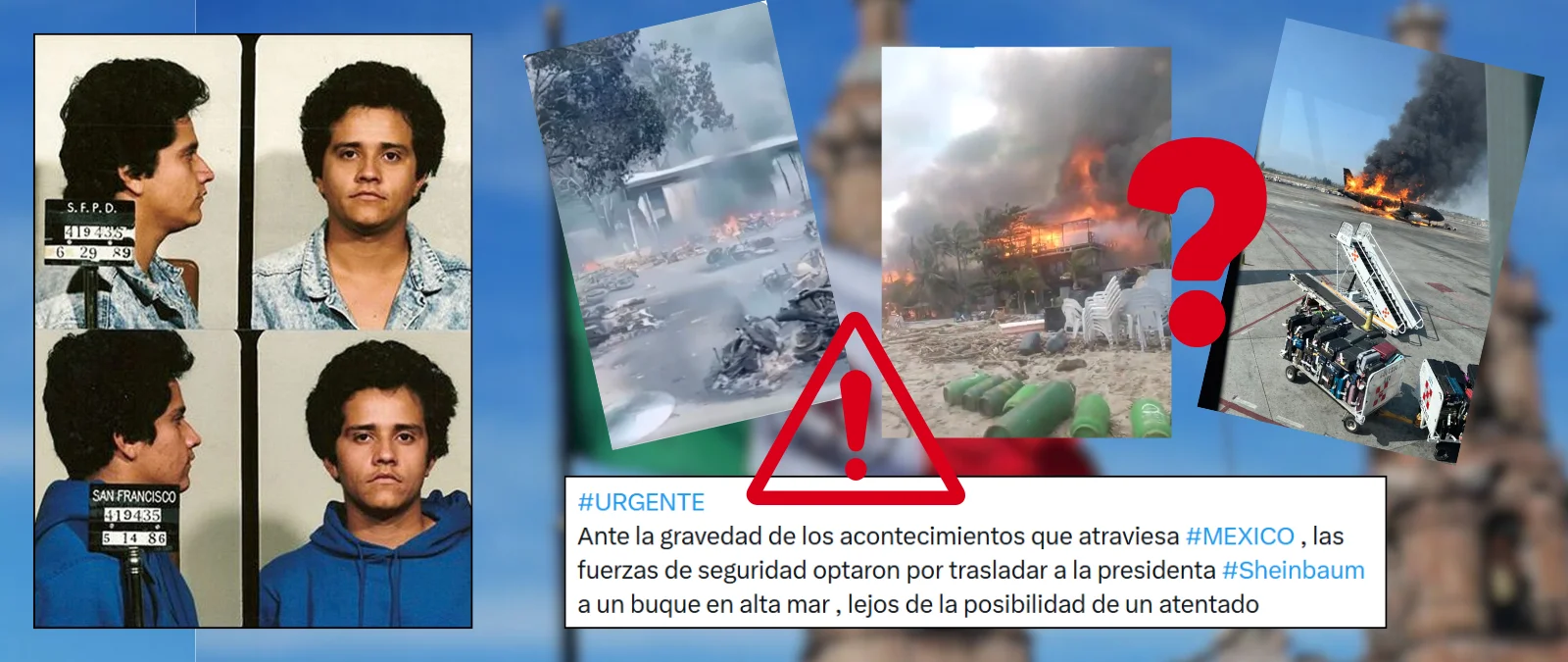

The Carlos Manzo Case: From Outrage to Conspiracy

“I don’t want to be just another mayor who is assassinated,” said Carlos Manzo, the Mexican mayor of Uruapan, who had been urging the federal government to provide more security to combat drug trafficking and organized crime. Months later, on November 1, 2025, as he led the Festival of Las Velas for Día de los Muertos in Uruapan, Michoacán, he was shot and killed. The streets of Uruapan quickly filled with people protesting and demanding justice.

In the fertile ground of emotion, the killing soon became a focus of speculation and conspiracy theories that moved in messages between Mexico and the United States.

According to DDIA, Carlos Eduardo Espina (of Uruguayan origin)—the leading Latino news influencer in the United States, according to the Pew Research Center—was “one of the first Latinos to speculate about a possible U.S. military response to Manzo’s assassination” in a November 3 post that went viral, generating more than 13,000 interactions in a week. In it, he said Washington had “begun to develop a plan for a ‘military operation’ in Mexico.” Other Latinos—some in Florida and New York—DDIA says, “went even further with their accusations” and, without evidence, “accused U.S. and Mexican opposition parties of allegedly orchestrating Manzo’s assassination ‘to justify an intervention’ against President Claudia Sheinbaum.”

The sequence of messages that followed the mayor’s killing “illustrates how some Mexican or Mexican American Latinos in the United States can remain connected to events in their country of origin,” DDIA analyzes.

Leaders and Influencers as Narrative Multipliers

The virality of a narrative often depends on endorsement by political figures or high-profile influencers, which lends credibility and visibility. As Braga explains, conspiracy theories “are driven largely by people who show very strong ideological convictions, a strong interest in politics, and by people who consume information within hyper-partisan ecosystems.”

Among those high-profile multipliers are:

Right-wing leaders: Some right-wing leaders in the United States (such as Donald Trump and members of Congress) and in Latin America (such as Presidents Nayib Bukele in El Salvador or Javier Milei in Argentina) often align around and amplify the same disinformation narratives, turning national events into regional ideological battles. “Spanish-speaking supporters (…) compared Noboa to conservative figures such as Donald Trump, Nayib Bukele, and Javier Milei, presenting the event not only as a national issue but as part of a broader regional ideological struggle,” the April 16, 2025 REDESCover newsletter notes.

Influencers as connectors: When influencers—whether on the right (such as Eduardo Menoni) or the left (such as Carlos Eduardo Espina)—comment on political events in the United States or Latin America, they serve as conduits for the spread of narratives.

High-profile endorsements: In the case of the detention of Kílmar Ábrego García—an Salvadoran whose removal from the United States and transfer to CECOT was described by the Trump administration as an “administrative error”—DDIA found that when Trump and Bukele spoke about the case, their messages spread “rapidly across all platforms, reaching approximately 3 million users within hours. The case became a flashpoint, illustrating how immigration-related narratives, especially when combined with political support, can achieve massive cross-platform virality.”

What circulates in messaging groups like WhatsApp often spills onto open social networks (or vice versa), and their algorithms play a crucial role in its spread. We know they do not prioritize evidence-based content, but rather what generates the most interactions.

Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari, author of Nexus, who has written about how modern information networks have enabled disinformation to spread quickly across borders, blames algorithms for promoting certain information over others. “If we ask who the most important editors are today, they are no longer human beings; they are AI: the algorithms that manage news on social media,” he says in an interview. He adds that the algorithms “have discovered that hate, anger, and greed generate engagement.”

Italian-Swiss writer Giuliano Da Empoli—author of The Hour of the Predators and The Engineers of Chaos—has also blamed algorithms and reflects on the political exploitation of chaos online: “Chaos is no longer the weapon of rebels, but the hallmark of those in power,” and he notes that disinformation is based on emotional manipulation, algorithmic targeting, and the strategic normalization of what is “false.”

In any case, what the review of all the DDIA newsletters produced between January and December 2025 on viral Spanish-language content in WhatsApp and Telegram groups—along with Factchequeado’s reporting—confirms is that once a concept (such as “political persecution” or the idea of a conspiracy) goes viral in a local context, sometimes driven by high-impact news events, it can quickly mutate and be repurposed to interpret events or figures in other countries. In this way, the movement of narratives “aligns through values and ideology, and no longer so strictly through language,” operating above national borders and linguistic differences.

* This investigation is part of “Los Desinformantes,” a series of investigations by LatamChequea—the network of Latin American fact-checkers—into different actors who spread disinformation in the region. This article was produced as part of the project “Promoting reliable information and fighting disinformation in Latin America,” coordinated by Chequeado and funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Factchequeado and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

**In 2024, Factchequeado received a grant from the Open Society Foundation, which was used to strengthen our work with Spanish-language media and to expand our work to civil society organizations in order to promote informed Latino communities.