This five-part investigation was conducted by Conexión Migrante and Factchequeado with support from the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) Disarming Disinformation program.

Puedes leer esta nota en español haciendo clic aquí.

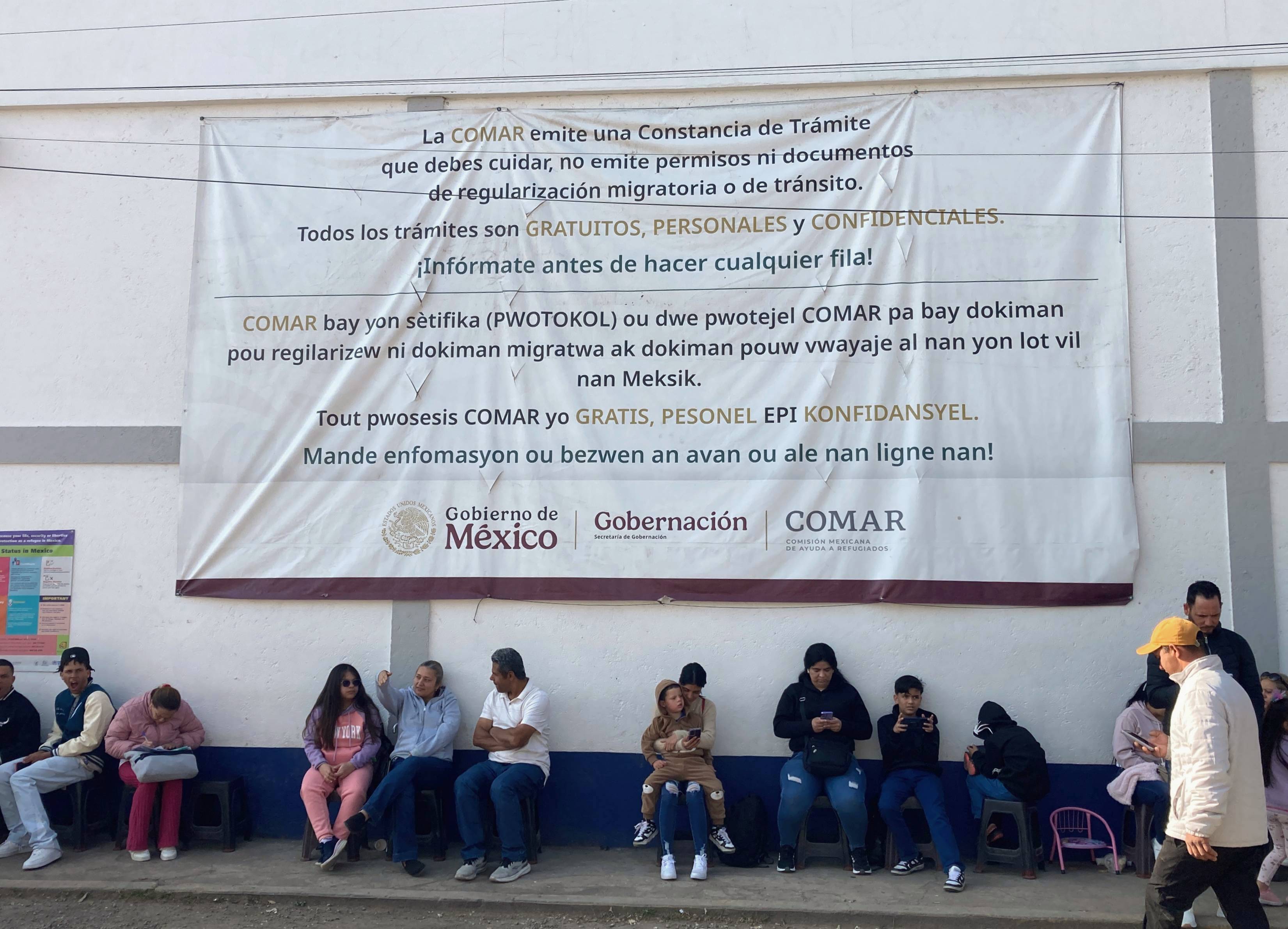

MEXICO. – Before sunrise, in an industrial area with few streetlights and sodden streets, dozens of immigrants are queuing in front of the new building of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR), in the outskirts of Mexico City. Some of them have paid 10 or 20 Mexican pesos to have a spot. Others were just hoping to be within the first two hundred to guarantee being seen. There are no civil servants to be found. There are no leaflets, guidelines or signs about the process.

Whether it’s due to ineffectiveness, lack of political will or indifference, Mexico’s government is the main culprit for disinformation on migration.

Their websites are not updated, the processes in place lead to offices that don’t exist, and there is almost no content about migration processes on their social media. And application offices for refugees are not on TikTok, the platform that has grown the most between migrants and where they get most of false or misleading answers, according to a survey done by Conexión Migrante, in alliance with Factchequeado.

Donald Trump militarized the border and closed the access for asylum and refuge when he returned to the presidency on January 20, 2025. Blocked by the US’ new policies, thousands decided to stay in Mexico to regularize their status, but instead of protection, they’re faced with a system that disinforms, offers little guidance, and exposes them to frauds and deception.

Between February and July 2025, we visited the offices handling refuge paperwork in Tapachula, Chiapas (at the south border), Monterrey, Nuevo León (in the north) and Naucalpan, State of Mexico (in the outskirts of Mexico City).

We filed ten applications for transparency and access to public information, and we analyzed dozens of social media accounts and hundreds of posts. We found the same pattern everywhere – public and systemic disinformation that facilitates the involvement of third parties with businesses and hoaxes.

Our own survey, conducted in 2023 and then again in 2025, shows that, in only two years, exposure to migration hoaxes went from 30% to 50%, while the number of people that claimed to have been affected increased by 10 percentage points, to 27.2%, according to survey responses collected between March and April 2025.

Foreign migration is not included in the presidential rhetoric

When Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum talks about migration, she usually refers to Mexican migrants in the US as “Mexico’s heroes” (see here and here), or “our migrant brothers and sisters.” But she rarely mentions the thousands of immigrants looking for an opportunity in Mexico.

Sheinbaum has said the word “migration” 405 times in press conferences since her government began on October 1st, 2024, and July 26, 2026, according to an analysis using the Sheinbaumpedia tool. She said “migrants in Mexico” twice (see here and here), “foreigners” three times (see here or here), and “COMAR” four times (see here or here).

Although the President doesn’t acknowledge the information gap, nor has she declared it state policy, the actions (and omissions) of her administration are aligned with those of the United States – to decrease the arrival and presence of migrants.

“The goal of the migration policy (in Mexico) and the omission of a refugee policy is part of the Government’s deal with the United States,” says Tonatiuh Guillén, Commissioner of the National Institute of Migration (INM) between December 2018 and June 2019, in an interview. His role as civil servant coincided with Trump’s first presidency.

Mexico reached a record number of refugee applicants in 2023 with 140,000 cases, claimed Andrés Ramírez, head of COMAR between 2019 and 2024. He also explained that, after being advised by human traffickers – “coyotes” in Spanish – migrants would ask for refuge only to obtain a certificate to request a Visitor Card for Humanitarian Reasons (TVRH) and travel with this permit without being stopped at the northern border.

Large numbers of migrants were arriving “without actually planning to stay in Mexico,” said Ramírez.

On paper, the federal government, under the label of “Mexican humanism,” claims to act under a policy of dignity and solidarity towards foreigners.

In terms of numbers, official statistics contradict the presidential discourse. Between January and June 2025, Mexico had an average of 666 arrests (119,183 total), called “presentations” by migration authorities – each one represents an “event” because the same person can be detained multiple times.

For deportations and voluntary returns, the average was 35 per day (6,209 total), according to the INM. From January to December 2024, the average was 3,384 arrests per day (1,234,698 total) and 57 daily deportations and voluntary returns (20,834 in total).

In practice, we noticed that in several attention points there are no official information desks or civil servants to guide people through their migration procedures, which can lead to the control and sale of appointments that are legally supposed to be free.

Some immigrants pay taxi fares of 30 to 40 dollars for trips that can be done with public transport because they are scared or lack direction. In different cities, consultants or lawyers make thousands by selling promises of legal regularization.

We contacted Mexico's presidential office, the refugee commission COMAR, and the National Immigration Institute for comment on systematic disinformation and the government's response to new U.S. immigration policies. None of the agencies responded.

The disinformative road of the “Mexican dream”

Irregular migrants in Mexico can regularize their status in three different ways: through the Immigration Law, for those with family members, spouses or jobs; international protection, including refugee status, which is managed by COMAR for people whose lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violations of human rights or other circumstances that greatly altered public order; and political asylum, managed by the Foreign Affairs Secretary for those who are being persecuted due to political motives or crimes.

The Mexican Government must assist migrants, but what is guaranteed by law is often not upheld in practice.

According to Article 19 of the Law on Refugees, Complementary Protection, and Political Asylum: “Applicants will have the right to receive clear, timely and free information about the recognition of their condition as refugees and the rights inherent to such condition, as well as the resources that this law and others grant.”

In the case of COMAR, our research observed a series of failures that do not comply with federal legislation:

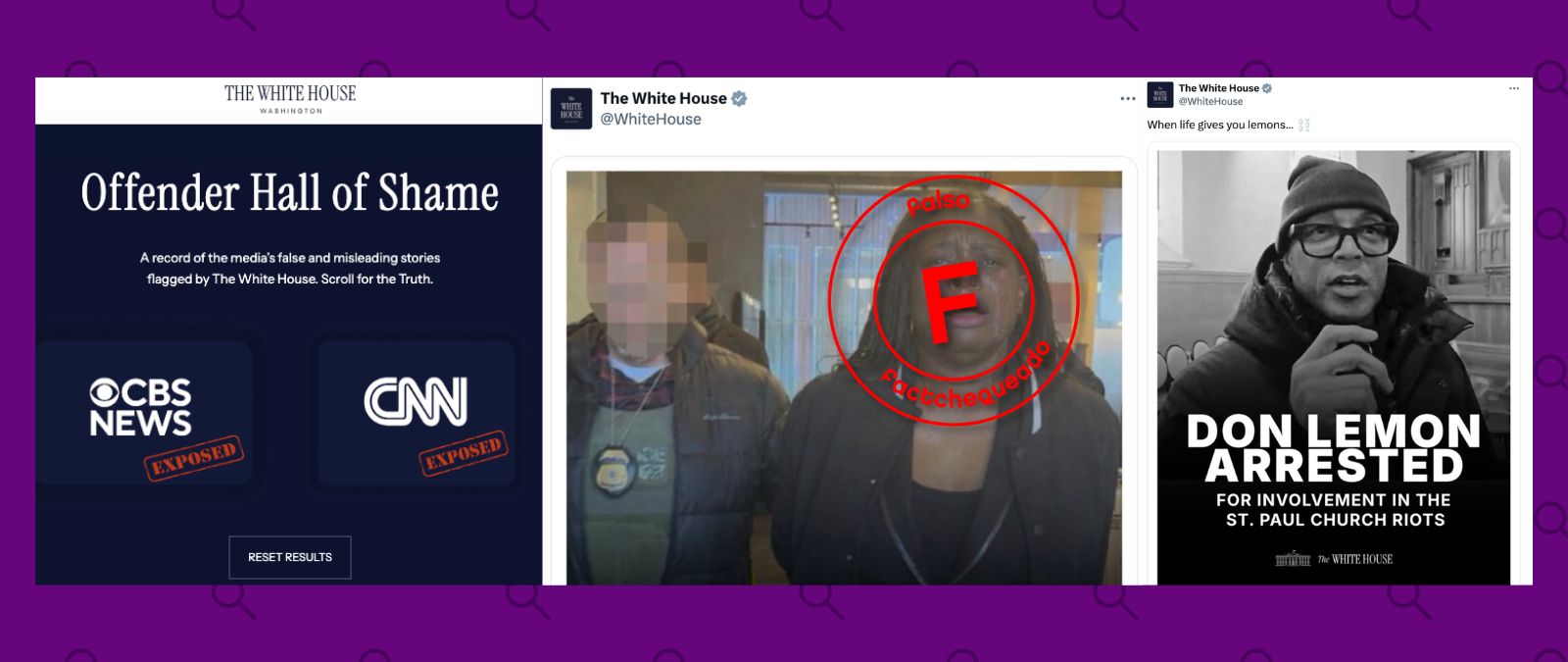

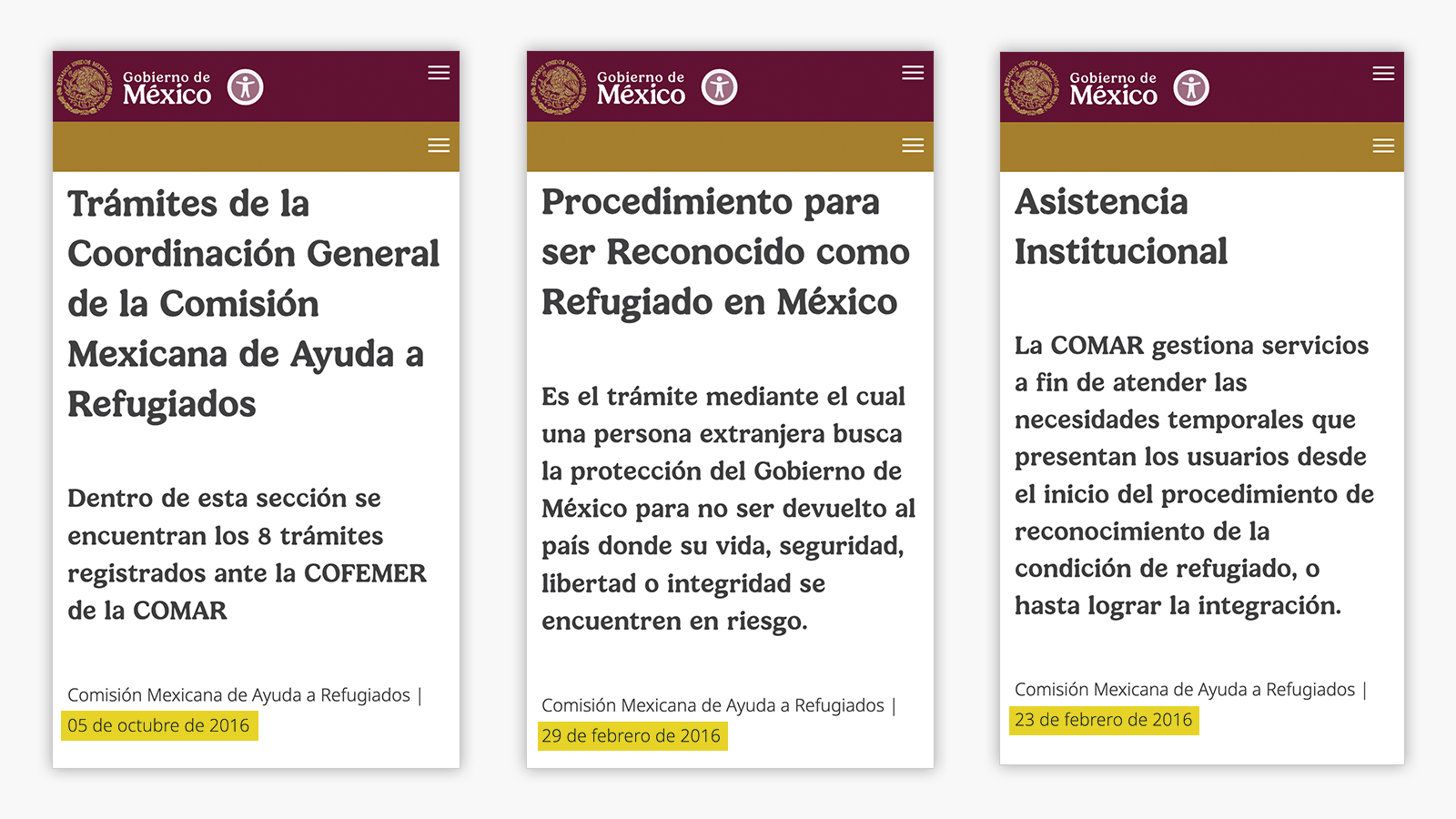

Outdated website: “Formalities and Procedures” has not been updated since 2016. Guidelines from 8 years ago lead to offices that don’t exist.

Social communication: “Press” section abandoned since November 2023 – during former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration, when it informed about refugee applications.

Social media without guidelines: from January to July 2025, we recorded that over 80% of posts on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram did not explain how to apply for refugee status. However, they do promote activities of their Director, Xadeni Méndez, appointed in January.

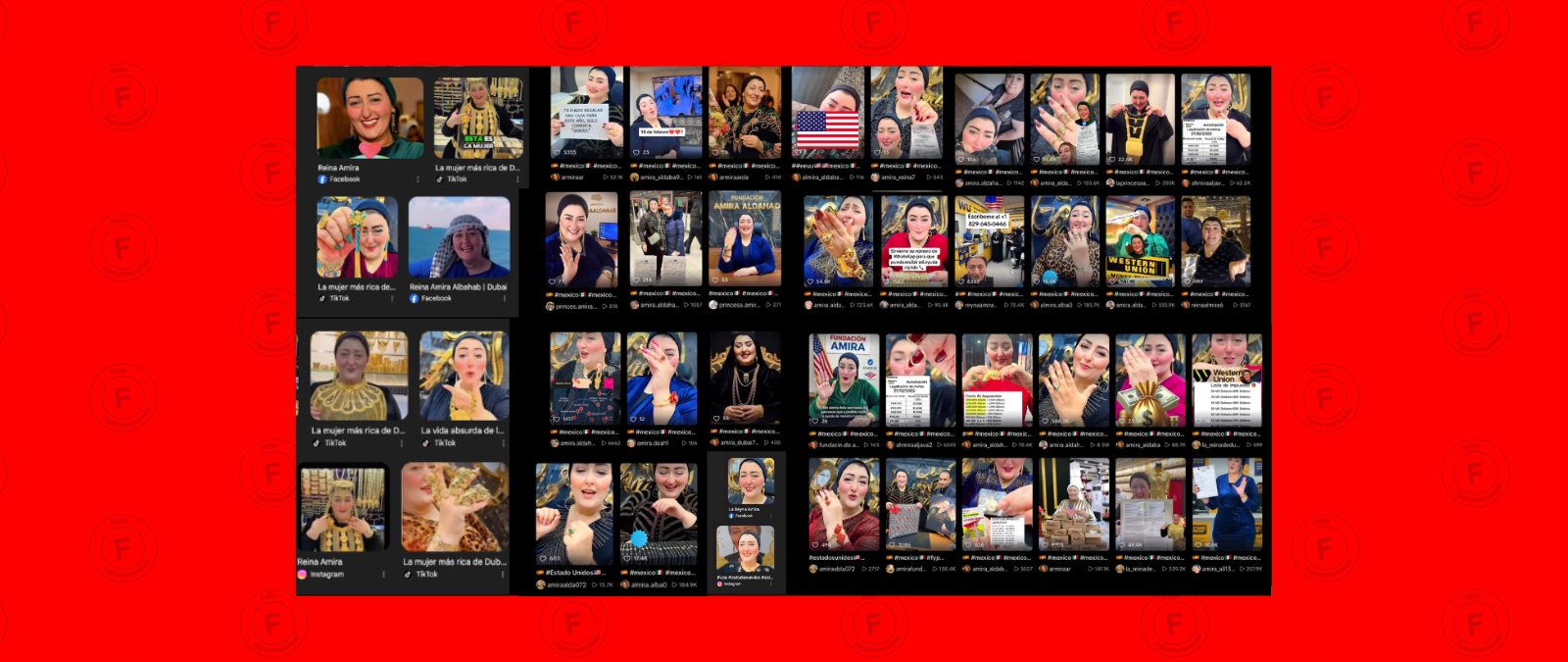

Absent on TikTok: there is no official account on the platform where most migrants search content, while there are at least 38 false accounts, some pretending to be Telemundo, Univision or using avatars like journalist Jorge Ramos, that managed to spread disinformation on immigration without being detected for a very long time.

Foreigners from other Latin American countries, or from much further away, like Iran and Syria, are now choosing Mexico as a permanent destination, and not just a bridge to the US. This trend has been accelerated by Trump’s toughened border policies.

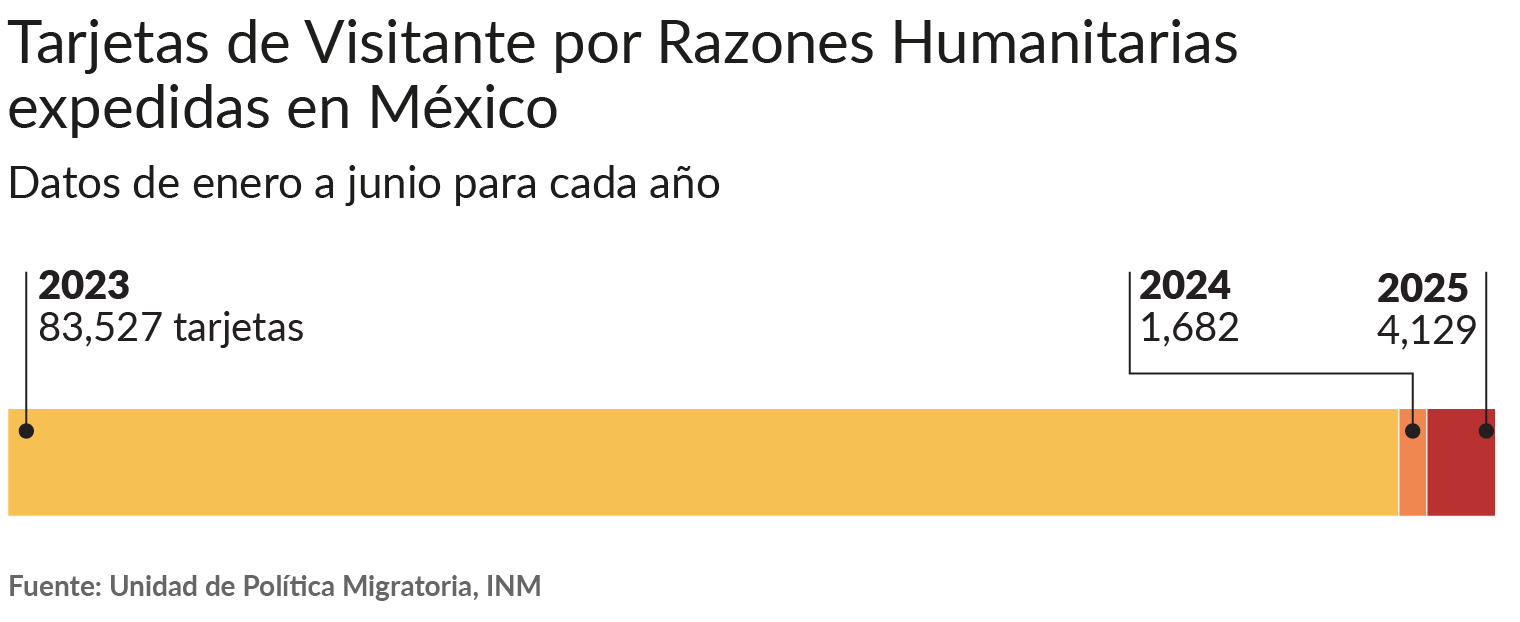

41% of people entering Mexico irregularly in 2024 claimed that it was their final destination, compared to 26% in 2023, according to a survey by ACNUR of 14,000 people. However, claims for refugee status in Mexico are decreasing, according to data obtained for this investigation from the Law on Transparency and Access to Public Information.

During the first seven months of 2025, COMAR managed an average of 240 refugee applications per day (50,639 in total) – more than half compared to the same period in 2024, when it was 344 (46,772 in total). In total, the number increased to 80,000 in 2024.

Businesses grow under an unhelpful State

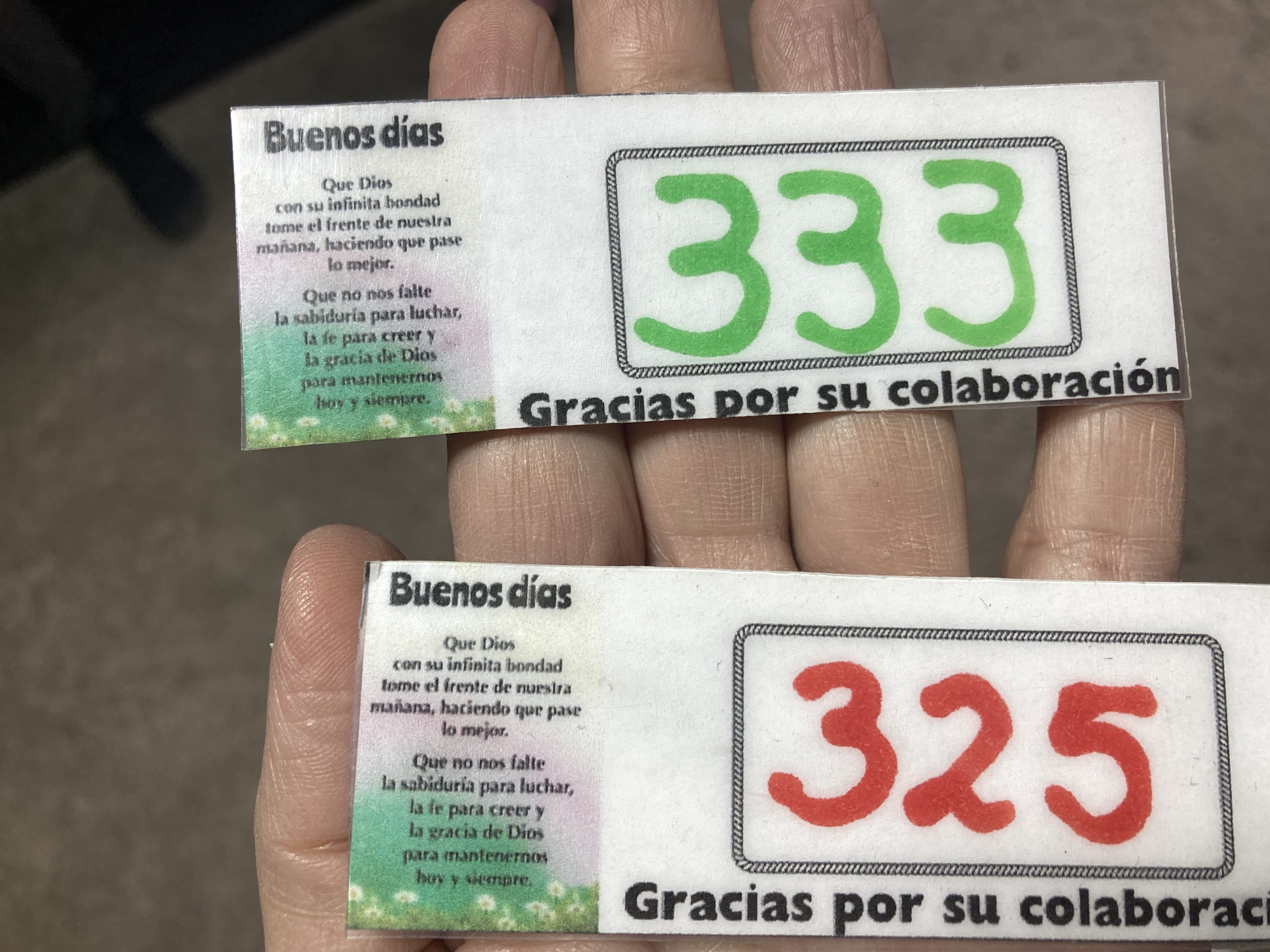

“Do you have a ticket? They’re only seeing two hundred people today,” says a young foreigner to people looking to claim refugee status at COMAR’s offices in Naucalpan, State of Mexico, in the outskirts of the Mexico City. The absence of official staff enables third parties to control access and sell tickets for services that are legally free.

Objections from residents lead COMAR to abandon their offices in Juarez, in the city center, after continuous complaints from locals about the camps set up by refugee applicants in the surrounding areas, according to reports from media outlets.

Headquarters opened twenty-five kilometers outside the city center, where it operates from a slaughterhouse in Naucalpan, an area affected by drug dealings and homicides.

Some migrants admitted having paid between 30 to 40 dollars to taxis for rides that they could have done in public transport, but they don’t feel safe to go by themselves or don’t know how to get there.

In the city of Tapachula, Chiapas, foreign applicants told us that until March of this year, a group of “Mexican queue jumpers” were selling appointments “threatening people with machetes and all.” Aliani, a 43-year-old immigrant seeking refuge, whose real name is not disclosed for safety concerns, had to pay.

People interviewed for this investigation explained that, in 2023, the year with a record number of refugee applications, members of organized crime controlled the place. They were described as men in vehicles, demanding payments to those organizing the queue and selling appointments for 50 USD (1,000 Mexican pesos).

We found law firms charging between 500 and 750 USD for consultancy services on refugee applications. “It depends on how you look,” said a young Cuban man. Lawyers prepare testimonies, rehearse interviews and escort people to COMAR’s front door.

In Tapachula, we went to one of these offices. One lawyer promised to guide us through the refugee application process if we paid 750 USD upfront. He also warned that if the applicant didn’t get refugee status it would be the applicant’s own fault or COMAR civil servants, but not the lawyer’s.

A refugee procedure that’s “in God’s hands”

Mexican legislation establishes 45 working days to complete a refugee procedure, although this period can be extended. INM civil servants are required to issue a provisional document expedited for humanitarian reasons, valid until the migration procedure is over.

In response to an information request, on May 15, 2025, 39,497 remained unprocessed, according to data that the government ceased publishing in December 2024.

To Aliani, an immigrant who submitted her request in January, civil servants asked her to wait for an email with information about when they would process her case. Three months went by without an answer. When she returned in May, she was told she had written her email address wrong, and she would have to wait another three months to start again.

Verónica, a 25-year-old Cuban woman, went to COMAR in Naucalpan on March 27, but she still hadn’t received any updates by July. “If you don’t get an email, you can only hope it’s well written. They can’t do anything else for you. It’s on God’s hands until you get it,” she said in an interview.

Besides processing fewer applications, COMAR lost 8% of its budget this year.

Lorena Cano, a lawyer of the Institute of Women in Migration (IMUMI), warns that when the INM doesn’t issue cards for humanitarian reasons during the process, it is breaking the law. If a person doesn’t have a resolution from COMAR, she says, “they are considered undocumented.”

False and misleading content spread on TikTok and Facebook

A study consisting of 169 posts gathered between July 2024 and June 2025 shows an ecosystem of disinformation on migration that operates mainly on TikTok and Facebook, which supports the findings of our own survey.

We documented 60 specific accounts spreading misleading content about migration processes, ranging from fake job offers to unreal visa promises.

Alleged law firms dominate disinformation on Facebook. The account "Robles & Robles Abogados" posted 52 times promotional content with hashtags like #abogadomigratorio (#migrationlawyer, 289 times), #residenciaMéxico (#Mexicoresidency, 171 times) and #COMAR (168 times). On TikTok, anonymous accounts proliferate promising things like “500 thousand H2 visas” and “a new way to enter the US legally.”

Trump’s border blockage transformed the discourse of these accounts. Users that used to sell the “American dream” are now promoting Mexico as “Plan B.” Some mix different narratives – they promise “a new legal way to enter the US,” “living in Mexico legally is possible,” or sell counselling for “residency and refuge in Mexico.”

Accounts like this one shared videos that falsely claim that “80% of the Mexican Army” was being deployed to the border, when Sheinbaum’s government deployed 10,000 soldiers of the National Guard, not the Army.

The account “Navarrete Abogados,” with 41,300 followers, posts videos that discourage people to seek refugee at COMAR while promoting private services. Applicants refer to raids under Trump’s administration and claim that similar raids are happening in Mexico as well because “they saw it on TikTok.”

“There is nothing on social media. How are we supposed to stay informed?” asks Yulian, a 34-year-old foreigner interviewed at COMAR, state of Mexico, in March 2025. “Media outlets don’t say anything. There’s only information on TikTok from other people,” claims Octavio, another refugee seeker.

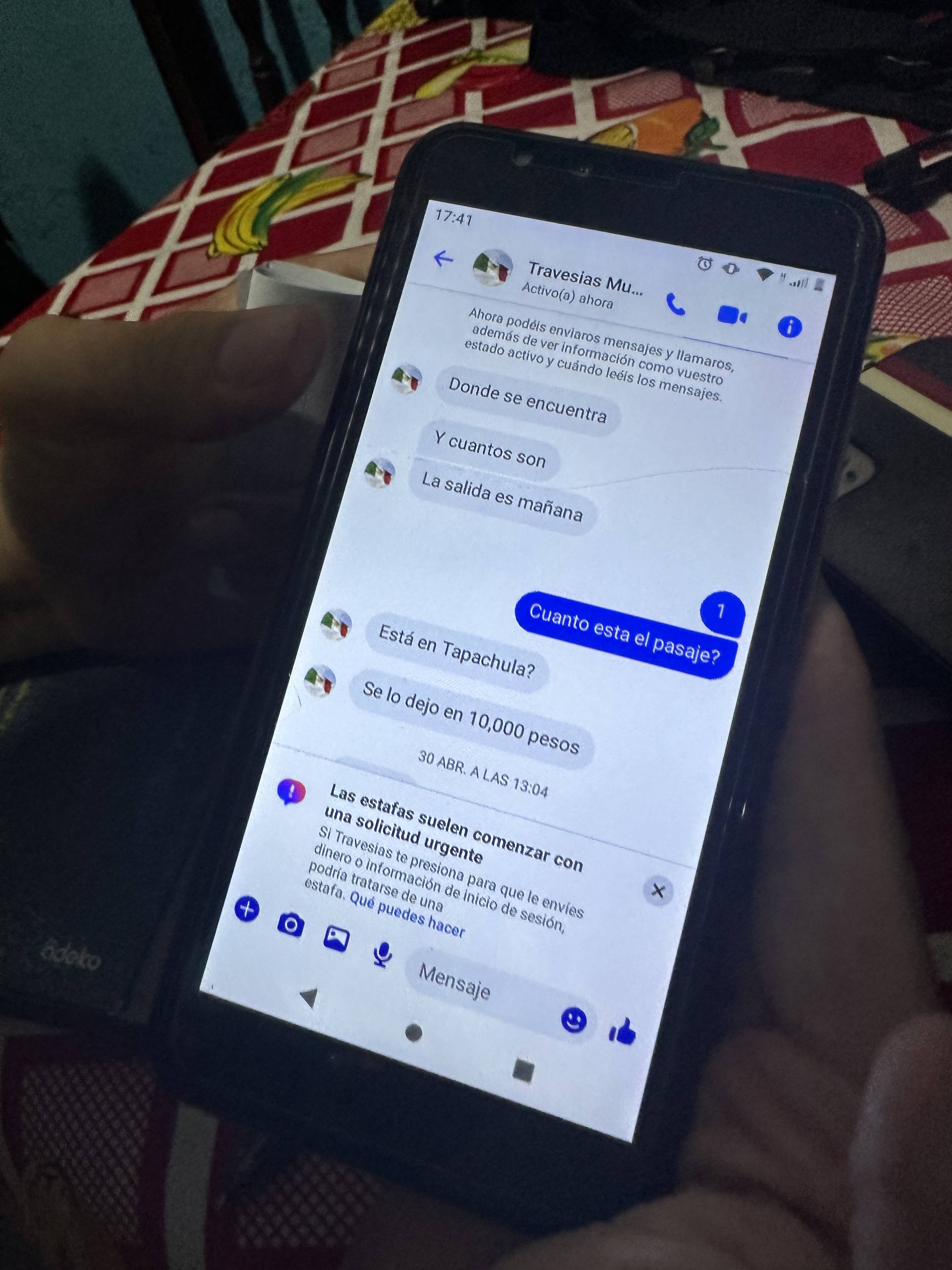

Scammers take advantage of immigrants’ desperation

Modus operandi: a foreign woman gets a call promising Canadian visas in exchange for a single payment of 1,000 USD. Scammers arrange to meet her at the offices of a mall in Santa Catarina, Nuevo Leon, near Monterrey, north of Mexico, which were closed due to a fraud investigation when visited by reporters from Conexión Migrante and Factchequeado in early May.

Restrictions on asylum and refugee processes in the United States have multiplied hoaxes targeted at legitimate organizations in the north of Mexico, near the border between the two countries.

One of the cases is what happened to civil organization Asylum Access. In March of this year, it uncovered attempts at fraud when it received notice of scammers pretending to be the NGO and some of its employees.

A lawyer from Asylum Access, who requested to stay anonymous, said that one of the most common frauds consists of offering migrants an “amparo” before they receive documents permitting them to travel legally across the country.

Only a judge can provide that document, which temporarily protects people against acts of authority, like detention or deportation, while their refugee process takes place.

Scammers trick them with false documents that only include the person’s name, and legal “wording” to look official. All in exchange for money and the promise to travel freely to other cities without being detained by Migrations.

“Institutional disinformation leaves migrants at the mercy of frauds and abuses. The lack of informative clarity is not a coincidence, but a structural part of the system,” claims IMUMI, a non-partisan NGO in Mexico. “They need clear and precise information about access to rights like healthcare, education, migration regularization, asylum and dignified work.”

The lack of useful content for migrants on official channels does not stop with social media. The Federal Public Defender's Office warns that “discretion by migration authorities and restricted access to observe their operations perpetuate systematic human right violations against people on the move.”

Despite the obstacles, many refugee seekers decide to build a life in the country.

“Mexico can offer opportunities as long as I’m working,” says Octavio, a 38-year-old migrant from the Caribbean that works in construction. “If I had known everything that happened, I would have never left my country. But I’m here now.”

Translation by Malena Saralegui.

*First of five-part series, "I'm Staying in Mexico"

Factchequeado is a verification media outlet built by a Spanish-speaking community to tackle disinformation in the United States. Do you want to be part of it? Join us and verify the content you receive by sending it to our WhatsApp +16468736087 or to factchequeado.com/whatsapp.

Read more:

Tapachula, the Border of Deception

Stories in Line: the Ordeal of Seeking Refuge in Mexico

Primera fecha de publicación de este artículo: 01/09/2025